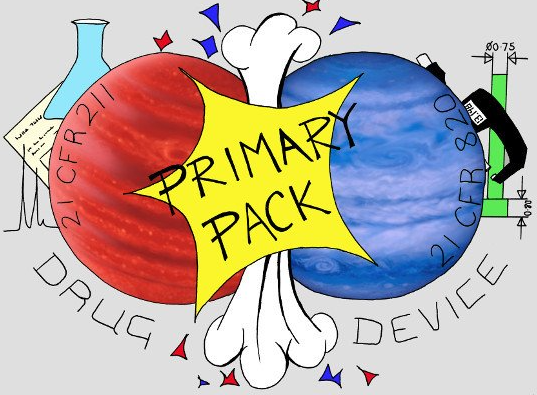

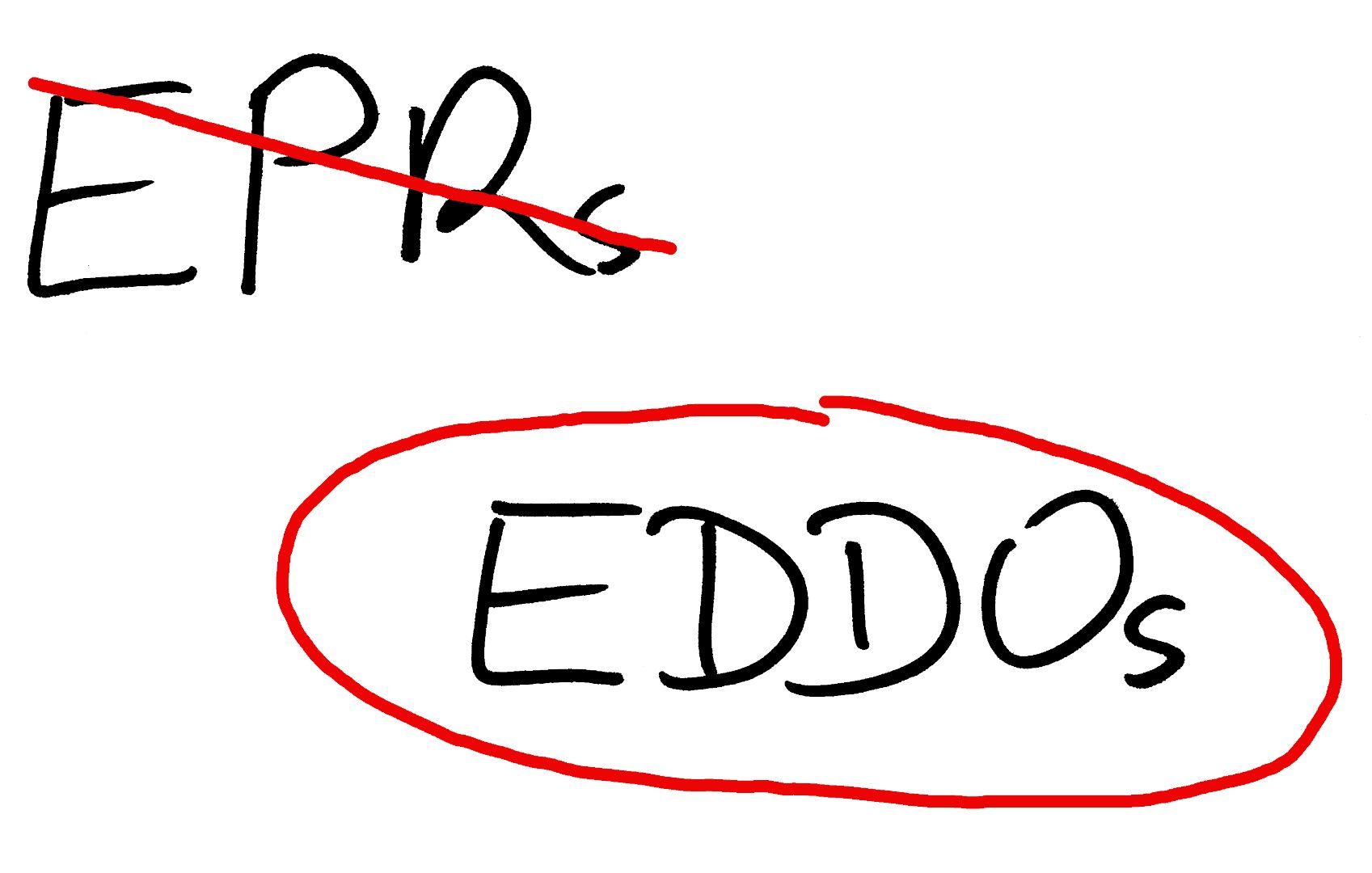

EDDOs (not Essential Performance Requirements)

It is approximately half what I hoped it would be. The balancing concept of ‘Essential Performance Requirements’ has been ditched, leaving just essential performance outputs, now called ‘Essential Drug Delivery Outputs’ (EDDOs). Instead of using existing traceability between (essential) inputs and outputs to derive EDOs, we now have a rather subjective filtering task to perform. This change is simply dismissed in a footnote as little more than re-naming.

However, I have left my original October 2023 EPR blog below for reasons of posterity...

While the FDA’s Office of Combination Products is working on a formal definition of Essential Performance Requirements behind closed doors, Industry is busy second-guessing. There are some clues to be had, and this is how I think it can work.

At first, I thought Essential Performance Requirements are an attempt to override (or undermine) the safety risk management process, dictating specific Essential Design Outputs regardless of evaluated risk. After wrestling with this unhappy thought for a while I realised that, actually, EPRs should perform a different role as the Guardians of Efficacy. Safety risk management stops devices from being unsafe, but it does not necessarily make them work reliably.

It is possible to design a drug delivery device that is safe, but does not always work. Consider an injection device that treats a chronic disease with regular injections. If an injection is missed because the device broke, the consequence may be a minor flare of symptoms. Risk management might evaluate the risk of occasional failure to inject and find it acceptable, when weighed against the benefit of the therapy. The device is safe, but it is not sufficiently reliable (or to put it another way; effective).

There is growing emphasis being placed on ensuring efficacy at the point of use, as well as safety. The language of efficacy has not yet crystalised, but when it comes to medical device functionality, I am going to coin the term ‘Essential Function’. A combination product performs many functions and a lot of them will be supporting acts to its raison d'être; the Essential Functions. Like a potato peeler must, when it comes down to it, peel potatoes.

Risk management still has a part to play. Remember the Hazards and Harms document in Part 4? Well, it can be used to generate a comprehensive list of product functions too. It is then an easy job to identify those raison d'être point-of-use functions that are the Essential Functions.

Design Input Requirements: That set of testable goals and constraints that we give to the designers to define the required device performance. Combinations of those Design Input Requirements give rise to product functions.

Now, armed with a list of Essential Functions, it is possible to match them up with their Design Input Requirement building‑blocks to identify the Essential Performance (Design Input) Requirements. Design Input Requirements are the logical place to highlight the desired core performance of the device to be developed. In that sense, it is completely independent of safety risk management which looks at risks embodied in the final design solution – the Design Output. They can both exist in harmony.

Since EPR Design Input Requirements trace to design outputs, we also find any efficacy‑based Essential Design Outputs (see Part 6) that risk management has overlooked. Device efficacy can now receive the same enhanced levels of rigour and control in test and manufacture as device safety. And as a bonus, we can have a transparent process that shows how we derive EPRs and then control them for our combination product.

Once again; this is my interpretation of the FDA’s enigmatic concept of Essential Performance Requirements. I’m sharing it because many of us are trying to integrate EPRs into our development processes and I hope it helps in some way.